Hierarchy

county

barony

civil parish

townland

Hierarchy

county

barony

civil parish

Explanatory note

- Gaeilge

the town of the uproar?

(Ní cinnte brí an fhocail deiridh.)Tá roinnt gnéithe spéisiúla ag baint le hainm an bhaile fearainn seo ina bhfuil an Comórtas Treabhdóireachta 2019 ar siúl.

Sa lá atá inniu ann fuaimnítear an siolla deiridh san ainm béarlaithe ar nós an fhocail Bhéarla train. Forbairt í seo atá cuíosach déanach, áfach, mar is cosúil gurb é a bhí ann roimhe sin a-tosaigh fada /aː/ (.i. leagan fada den ghuta san fhocal Béarla ran), agus gurb in é a bhí i gceist leis an litriú -trane an chéad lá. Cuir i gcás fuaimniú an ainm phearsanta Seán i nGaeilge Dhún na nGall inniu .i. /ʃaːn/ — sin é a bhí i gceist leis an litriú béarlaithe Shane i dtosach báire, ach d’imir an fhorbairt chéanna ar an ainm Béarla sin agus deirtear /ʃeːn/, /ʃeɪn/ inniu ar ndóigh. Forbairt nádúrtha fhoghraíochta faoi ndear é seo ina n-ardaítear /aː/ go /eː/ (cuid den athrú mór sa Bhéarla ar a dtugtar an ‘Great Vowel Shift’), seachas tionchar an litrithe -ane féin. (Mar shampla, tá Naas seanbhunaithe mar leagan béarlaithe den logainm An Nás i gContae Chill Dara, litriú a chuireann /naːs/ le a-fada in iúl go soiléir — ach d’fhorbair fuaimniú an logainm Bhéarla go /neːs/, /neɪs/ beag beann ar an litriú sin.) Sa logainm seo idir chamáin tá bearna mhór san fhianaise ach bhí an próiseas faoi sheol sa chéad leath den 19ú haois ar a dhéanaí — féach an litriú ‘Ballintrain’ i Leabhar na nDeachúna (1833), taobh le ‘baile an tráin’, an fuaimniú áitiúil coimeádach, de réir dealraimh, san Ainmleabhar (1839). (Tabhair faoi deara nach féidir brath ar 1655 ‘Ballitraine’ DS, 1660c. ‘Ballytraine’ BSD, 1685 ‘B:train’ Hib. Del. mar fhianaise ar an bhfuaimniú nua sin sa dara leath den 17ú haois — tá na trí fhoinse úd Down Survey, Book of Survey and Distribution agus Hiberniæ Delineatio gaolmhar le chéile agus is minic a bhíonn miondifríochtaí le fáil iontu nach bhfuil le fáil i bhfoinsí neamhspleácha comhaimsearthacha, m.sh. sa chás seo 1631 ‘Ballintrane’, 1659 ‘Ballitrane’.)

Dá bhrí sin is féidir glacadh le foirmeacha luatha traslitrithe ar nós 1545 ‘Ballyntrane’, 1559 ‘Ballintrane’, 1631 ‘Ballintrane’ mar léiriú ar fhuaimniú cosúil le *Ballintraan /ˌbalɪnˈtraːn/. Ar an gcéad fhéachaint ní léir cén focal Gaeilge a d’fhéadfadh a bheith taobh thiar den fhuaimniú béarlaithe sin — ach tagann foirmeacha luatha eile anuas chugainn a chaitheann solas ar a bhunús, mar atá 1547 ‘Ballytrohyn’ agus 1551 ‘Ballytrahin’ (aithris ar iontráil 1551 is ea 1563 ‘Ballytrahin’ agus 1604 ‘Balletrahin’). Is cosúil freisin gur míléamh ar *‘-trahyne’ atá sa litriú 1549 ‘Ballyntrayrne’. Tugann na foirmeacha seo fuaimniú béarlaithe ar nós *Ballintrahin /ˌbalɪnˈtrahɪn/ le fios. (Cuireann siad -n caol deiridh san ainm Gaeilge in iúl freisin, rud a d’éascódh an t-ardú thuasluaite ó /aː/ go /eː/ dá mbeadh sleamhnán le clos.) Ní leaganacha truaillithe iad seo, mar is amhlaidh is féidir iad a réiteach leis na foirmeacha eile úd ach gné spéisiúil de chuid logainmneacha Gaeilge Chúige Laighean a thuiscint.

Tá cuid mhaith logainmneacha i sean-Chúige Laighean ina bhfuil -h- idir dhá ghuta ghairide le feiscint sna foirmeacha traslitrithe luatha, ach go n-imíonn an -h- seo astu níos déanaí go ndéanann aon ghuta fada amháin den dá ghuta a bhí timpeall air. Mar shampla, in oirdheisceart Chill Mhantáin atá An Muine Leathan “the broad thicket” (#55171): Moneylane atá air sin i mBéarla inniu (arís, is a-ghuta fada a bhí á chur in iúl leis an litriú sin an chéad lá, mar a bheadh *Money-laan) ach faighimid ‘Monylahan’ i gcáipéis ó *c.*1660. Sa chontae céanna, d’aithin Seán Ó Donnabháin an logainm Curraghlawn ag bun Chruacháin (‘Curraghlaan’ i Leabhar na nDeachúna) mar réadú áitiúil ar An Currach Leathan “the broad wet land” (#55892) — bhí cur amach aige ar an gcanúint áitiúil ó bheith ag labhairt le sean-Ghaeilgeoirí gar do Shíol Éalaigh (31/12/1838) agus do Thigh na hÉille (3/1/1839) (cf. LSO CM 121, 140) sa cheantar céanna — agus go deimhin scríobh sé ‘Currach leáthan’ le síneadh fada chun aird a tharraingt ar an bhfuaimniú sin. Agus i gContae Cheatharlach féin, taobh thuaidh den Tulach atá An Ráth Leathan “the broad ring-fort” (#3522), fuaimnithe ‘Raith laan’ ag muintir na háite i 1839 agus litrithe ‘Rathlahyne’ i 1601 (Rathlyon an litriú Béarla anois).

D’imir an fadú cúitimh seo ar ghutaí eile freisin ar chailliúint -th- dar ndóigh. Tá baile fearainn i bparóiste Thigh Mochua i gContae Laoise, gairid go leor do bhaile Cheatharlach, ar a dtugtar Knocklead sa Bhéarla (a bhfuil e-ghuta fada sa dara siolla, ar nós an fhocail Bhéarla laid). I 1838 dúirt seanduine ón bparóiste sin le Seán Ó Donnabháin gur ‘Cnoc léad’ a bhí ar an áit sa Ghaeilge agus gur “hill of the breadth” ba bhrí leis. Gan amhras is é Cnoc Leithid (#1417562) an t-ainm a bhí i gceist aige — agus an uair seo is e-ghuta a ndearna fadú cúitimh air de bharr an -th- a chailliúint sa chanúint. Sampla eile den fhocal céanna i gContae Cheatharlach is ea Baunleath, in aice Sheanleithghlinne (ar ghlaoigh cuid de mhuintir na háite /bɑːnˈleːət/ air sna 1990í, mar a bheadh ‘Bawn-layet’) — Bán Leithid “lea-ground of (the) breadth” (#3433) an t-ainm Gaeilge.

Tá fianaise ar an nós seo le fáil i logainmneacha eile i ndeisceart Bhaile Átha Cliath, i gCill Dara, in oirthear Uíbh Fhailí agus i Loch Garman, chomh maith le Cill Chainnigh. Tá oiread samplaí againn is a thugann orainn a mheas gur cosúil gur fhíorghné é den chanúint dhéanach Ghaeilge sa chuid seo de Chúige Laighean, agus nach é lagú an -h- idirghutaigh de bharr an phróisis bhéarlaithe faoi ndear. (Bhí an gné céanna i nGaeilge Chúige Uladh lasmuigh de Thír Chonaill (cf. www.doegen.ie), agus gan dabht tá sé le clos sa lá atá inniu ann i gcuid de Chonamara agus in Oileáin Árann, mar shampla, mar a ndeirtear lea’an /lʹaːn/, a’air /aːrʹ/, cea’air / kʹaːrʹ/ le haghaidh leathan, athair, ceathair, srl.)

Nuair a rinne Eoghan Ó Comhraí an obair pháirce sa bhaile fearainn seo i mí Lúnasa 1839 scríobh sé ‘baile an tráin’ san Ainmleabhar agus ‘(tsruthain(?))’ díreach i ndiaidh an fhocail dheireanaigh. (Ní bhfuair Ó Comhraí an t-eolas seo ó Ghaeilgeoirí áitiúla, mar ní raibh aon Ghaeilge sa pharóiste seo an uair úd; bhí de nós aige an fuaimniú Béarla a bhreacadh síos as Gaeilge mar seo.) Is mór an ghéarchúis a bhí aige cailliúint -th- a thuairimiú, go háirithe ó nach raibh teacht aige ar na foirmeacha luatha úd a thaispeánann go raibh -h- ann ó bhunús (1551 ‘Ballytrahin’, srl.) — ach ní raibh aige ach cuid den cheart, mar ní thagann an fhianaise stairiúil le sruthán in aon chor. Ní bheimis ag súil le -th- a chailliúint roimh ghuta fada, go háirithe chomh luath le 1559 ‘Ballintrane’ (cf. 1574 ‘Sroghanesillaghe’, 1663 ‘Sruhane’ .i. Sruthán Saileach (#54885) i gCill Mhantáin agus an ainm stairiúil 1654 ‘Srahannavallagh’, ‘Shrahannavally’ .i. Sruthán an Bhealaigh, seanainm ar abhann teorann i gContae Laoise (féach #28118)). Is féidir sraithín “little holm, river meadow” a chur as an áireamh dá réir sin chomh maith. Ghlac Seán Ó Donnabháin le ‘Baile an tsrotháin, town of the streamlet’ ach bhí sé féin in amhras faoi — thuairimigh sé ‘baile an tréin, town of the mighty man’ freisin, ach faoi mar a chonaiceamar thuas ní réiteodh an é-fada sin leis na foirmeacha luatha.

Más ea, tá an chruth seo a leanas ar an bhfianaise stairiúil dar linne:

Ballintrane (.i. *Ballintraan) < Baile an *Tr(e)áin (< Tr(e)a’ain) (cf. 1559 ‘Ballintrane’) < Baile an Tr(e)athain (?) (cf. 1547 ‘Ballytrahin’)

Measaimid go mb’fhéidir gur treathan atá san eilimint deiridh, focal a d’fhorbair as SG tríath ‘farraige’ agus a raibh an réimse bríonna ‘farraige’–‘farraige stoirmiúil’–‘stoirm’ aige sa tSean-Ghaeilge, agus ina dhiaidh sin ‘gleo, fíoch feirge, toirníl’, srl. Tagann sé i gceist (go hindíreach) sa logainm Dún Contreathain “the fort of Cú Treathain” (#44838) ar chósta Chontae Shligigh, a bhfuil an t-ainm pearsanta Cú Treathain “hound of the sea; hound of (sea-)fury” mar cháilitheoir ann (díol spéise na foirmeacha seo a leanas: 1249 ‘go Dún Contreathain’, 1584 ‘Downchentrahan’, 1585 ‘Dun-contrehain’, 1587 ‘Donghentrayne’, 1593 ‘Doonkintreain’, 1617 ‘Douncontrahan’, 1633 ‘Doncontrain’; foirm áitiúil Ghaeilge 1836 ‘Donach an Treathain’). Soláthraíonn Ó Duinnín tuilleadh fobhríonna le treathan, mar atá “a foot, a track, or trace”.

Ní léir dúinn anois cé acu brí a bhí faoi thagairt sa logainm Baile an Treathain an chéad lá, ach más amhlaidh gur “the town of the uproar, tumult” nó a leithéid a bhí i gceist (cf. Baile an Racáin (?) “the town of the tumult” (#37995) i gContae na Mí), díol spéise an t-ainm a baisteadh ar an gcnoc 2km siar ón mbaile taobh leis an N80 .i. An Cnoc Bodhar/Knockbower “the ‘deaf’ hill (hill of the dull sound)” (#3338)!

- English

the town of the uproar?

(The meaning of the last word is uncertain.)The name of the townland hosting the 2019 Ploughing Championships has a number of interesting features.

The last syllable of the name is pronounced today like the English word train /treːn/, /treɪn/. This is a late development, however, as it appears to have previously contained a long front a-vowel /aː/ (i.e., a long version of the vowel in the English word ran); this is what was first intended by the spelling -trane. Compare the pronunciation of the personal name Seán in Donegal Irish, i.e. /ʃaːn/ — the English spelling Shane originally represented a similar pronunciation, until the anglicized name underwent the regular development which raised /aː/ to /eː/, /eɪ/ leaving the English name familiar to us today as /ʃeːn/, /ʃeɪn/. This sound change is a natural phonetic development (part of the Great Vowel Shift), and has nothing to do with the influence of the spelling -ane. (See for example the spelling Naas which is long established as the anglicized version of the Kildare placename An Nás — this quite clearly represents /naːs/ with the original long a-vowel, but in spite of this spelling the English name of the town has changed to /neːs/, /neɪs/.) There is a gap in the evidence for Ballintrane but this process was underway by the 19th century at the latest — compare the newer pronunciation in the spelling ‘Ballintrain’ in the Tithe Applotment Books (1833) with the apparently more conservative local pronunciation ‘baile an tráin’ in the Ordnance Survey Namebook (1839). (We cannot rely on 1655 ‘Ballitraine’ DS, 1660c. ‘Ballytraine’ BSD, 1685 ‘B:train’ Hib. Del. as evidence of the new pronunciation as early as the 17th century — these three sources Down Survey, Book of Survey and Distribution agus Hiberniæ Delineatio are interdependent and often contain the same error not found in unrelated contemporary sources; in this case see 1631 ‘Ballintrane’, 1659 ‘Ballitrane’.)

With this in mind we can take early transliterated forms such as 1545 ‘Ballyntrane’, 1559 ‘Ballintrane’, 1631 ‘Ballintrane’ as indications of a pronunciation such as *Ballintraan /ˌbalɪnˈtraːn/. At first it is difficult to see what Irish word this might represent — but other early references happen to survive which cast light on the Irish form, namely 1547 ‘Ballytrohyn’ and 1551 ‘Ballytrahin’ (1563 ‘Ballytrahin’ and 1604 ‘Balletrahin’ are reiterations of the 1551 entry). It is also likely that 1549 ‘Ballyntrayrne’ is a misreading of *‘-trahyne’. These forms indicate an anglicized pronunciation such as *Ballintrahin /ˌbalɪnˈtrahɪn/. (They also indicate a slender final -n in the Irish name, which would facilitate the phonetic development mentioned above.) These forms might initially be considered corruptions, but in fact they can be explained by reference to another interesting feature of Irish placenames in Leinster.

There are many placenames in the ancient province of Leinster (i.e., excluding Louth, Meath, Westmeath, Longford and west Offaly) that show a -h- between two short vowels in early transliterated forms which disappears in later references, with the lengthening of the two surrounding short vowels into one long vowel. For example, the townland Moneylane in southeast Wicklow (a spelling intended to represent the pronunciation Money-laan with a long a-vowel) is spelled ‘Monylahan’ *c.*1660 — the Irish name is An Muine Leathan “the broad thicket” (#55171). In the same county, John O’Donovan was able to recognize the placename Curraghlawn at the foot of Croghan Mountain (‘Curraghlaan’ in the Tithe Applotment Books) as a local form of An Currach Leathan “the broad wet land” (#55892) — he would have been familiar with the local Irish dialect having conversed with elderly Irish speakers near Shillelagh (31/12/1838) and Tinahelly (3/1/1839) (LSO CM 121, 140) in the same district — and indeed he wrote the Irish name with a síneadh fada, ‘Currach leáthan’, to emphasise the point. In County Carlow itself, Rathlyon to the north of Tullow was pronounced ‘Raith laan’ by the locals in 1839, and we find it spelled ‘Rathlahyne’ in 1601 — the Irish name is An Ráth Leathan “the broad ring-fort” (#3522).

Of course, this compensatory lengthening upon the loss of -th- happened in the case of other vowels too. There is a townland in the parish of Timahoe in County Laois, not too far from Carlow town, called Knocklead in English (the second part pronounced with a long e-vowel, something like the English word laid). In 1838 an old man from that parish told John O’Donovan that the Irish name of the place was ‘Cnoc léad’ and that it meant “hill of the breadth”. The name in question is Cnoc Leithid (#1417562), this time with an e-vowel being lengthened to compensate for the loss of the -th- sound in the local Irish dialect. Another example of the same word is Baunleath beside Oldleighlin in County Carlow (which some of the locals still pronounced /bɑːnˈleːət/ in the 1990s, as if ‘Bawn-layet’) — the Irish name is Bán Leithid “lea-ground of (the) breadth” (#3433).

Further evidence for this tendency is found in the placenames of south Dublin, Kildare, east Offaly and Wexford, as well as in Kilkenny. There are sufficient examples for us to consider it likely that this was a genuine feature of the late Irish dialect of this part of Leinster, rather than being due to the weakening of intervocalic -h- in the anglicization process. (Note that this feature was found in other Irish dialects as well, such as the Irish spoken in Ulster outside of Donegal (cf. www.doegen.ie), and of course it is still to be heard in the Irish spoken in parts of Conamara and Oileáin Árann, for example, where they say lea’an /lʹaːn/, a’air /aːrʹ/, cea’air / kʹaːrʹ/ for leathan, athair, ceathair, srl.)

When Eugene O’Curry conducted the fieldwork in this townland in August 1839 he wrote ‘baile an tráin’ in the Namebook and wrote ‘(tsruthain(?))’ directly after the last word. (O’Curry did not obtain this information from local Irish speakers, as there was no Irish spoken the parish at this time; he merely had a habit of writing down the local English pronunciation in Irish.) His suggestion of the loss of -th- was very astute, especially given that he had no access to those early historical references which showed an original -h- (1551 ‘Ballytrahin’, etc.). However, he was only half right, as the evidence does not support sruthán: we would not expect the loss of -th- before a long vowel, and certainly not as early as 1559 ‘Ballintrane’ (cf. 1574 ‘Sroghanesillaghe’, 1663 ‘Sruhane’ for Sruthán Saileach (#54885) in Wicklow and the historical name 1654 ‘Srahannavallagh’, ‘Shrahannavally’, i.e., Sruthán an Bhealaigh, the name of a boundary stream in County Laois (féach #28118)). The word sraithín “little holm, river meadow” can be discounted for the same reason. John O’Donovan went with ‘Baile an tsrotháin, town of the streamlet’ but with some reservation — he also proposed ‘baile an tréin, town of the mighty man’! As we have seen before this second suggestion cannot be correct either, as the long e-vowel is not historical.

In short, we believe that the historical evidence can be viewed as follows:

Ballintrane (i.e., *Ballintraan) < Baile an *Tr(e)áin (< Tr(e)a’ain) (cf. 1559 ‘Ballintrane’) < Baile an Tr(e)athain (?) (cf. 1547 ‘Ballytrahin’)

We think that the final element may be the word treathan, a derivative of OIr. tríath ‘sea’ which had the semantic range ‘sea’–‘stormy sea’–‘storm’ in Old Irish, and later ‘uproar, fury, thundering’, etc. The word is an indirect part of the placename Dún Contreathain “the fort of Cú Treathain” (#44838) on the coast of County Sligo, in which the qualifying element is the personal name Cú Treathain “hound of the sea; hound of (sea-)fury” (the following forms are worthy of note here: 1249 ‘go Dún Contreathain’, 1584 ‘Downchentrahan’, 1585 ‘Dun-contrehain’, 1587 ‘Donghentrayne’, 1593 ‘Doonkintreain’, 1617 ‘Douncontrahan’, 1633 ‘Doncontrain’; and the reinterpreted local Irish form 1836 ‘Donach an Treathain’). Dinneen gives a few further secondary meanings for treathan, namely “a foot, a track, or trace”.

It is difficult at this remove to see which of these meanings may have been intended in the placename Baile an Treathain, but if it did indeed mean “the town of the uproar, tumult” or similar (cf. Baile an Racáin (?) “the town of the tumult” (#37995) in County Meath), it is interesting to note the name given to the hill beside the N80 2km west of the townland — An Cnoc Bodhar/Knockbower “the ‘deaf’ hill (hill of the dull sound)” (#3338)!

Centrepoint

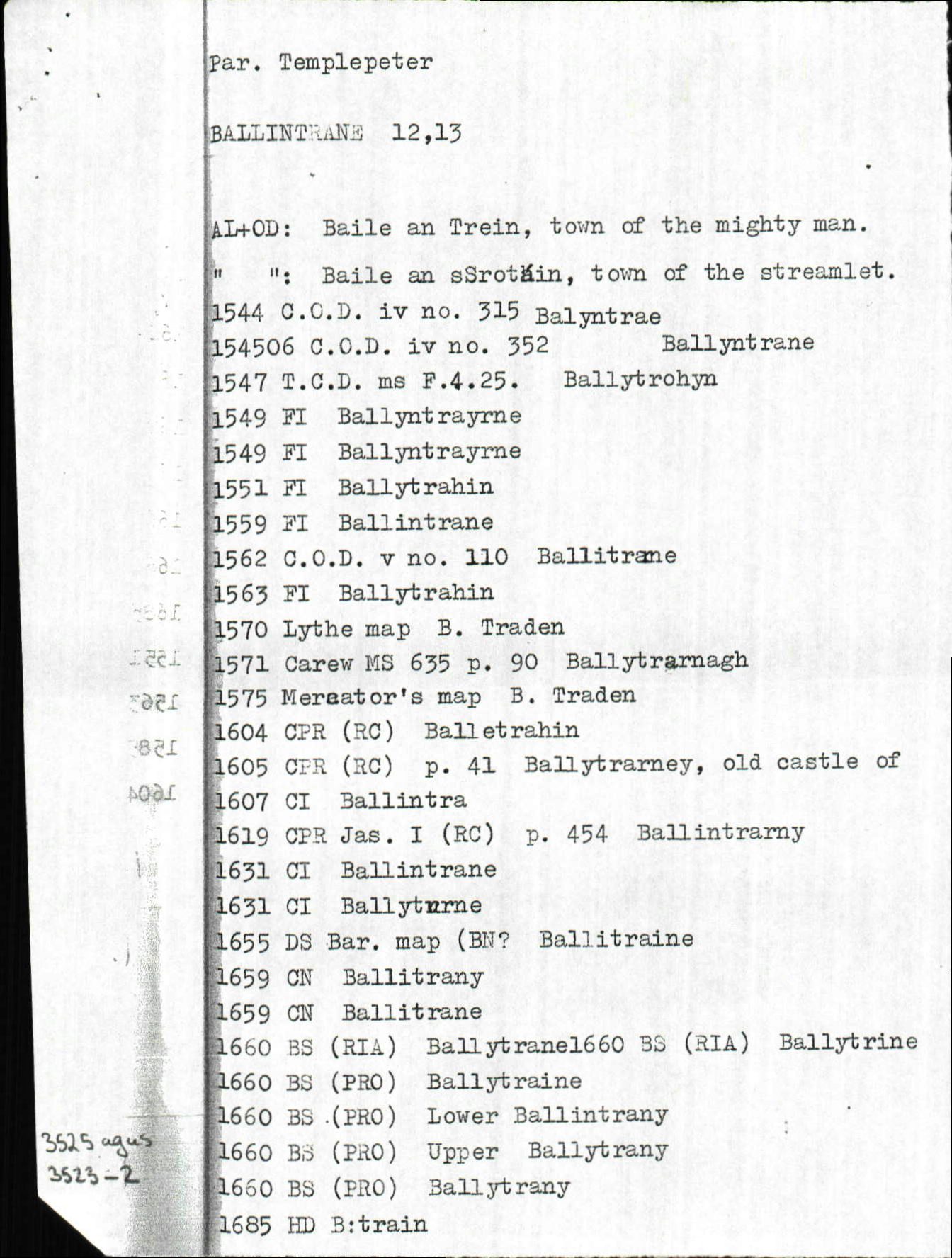

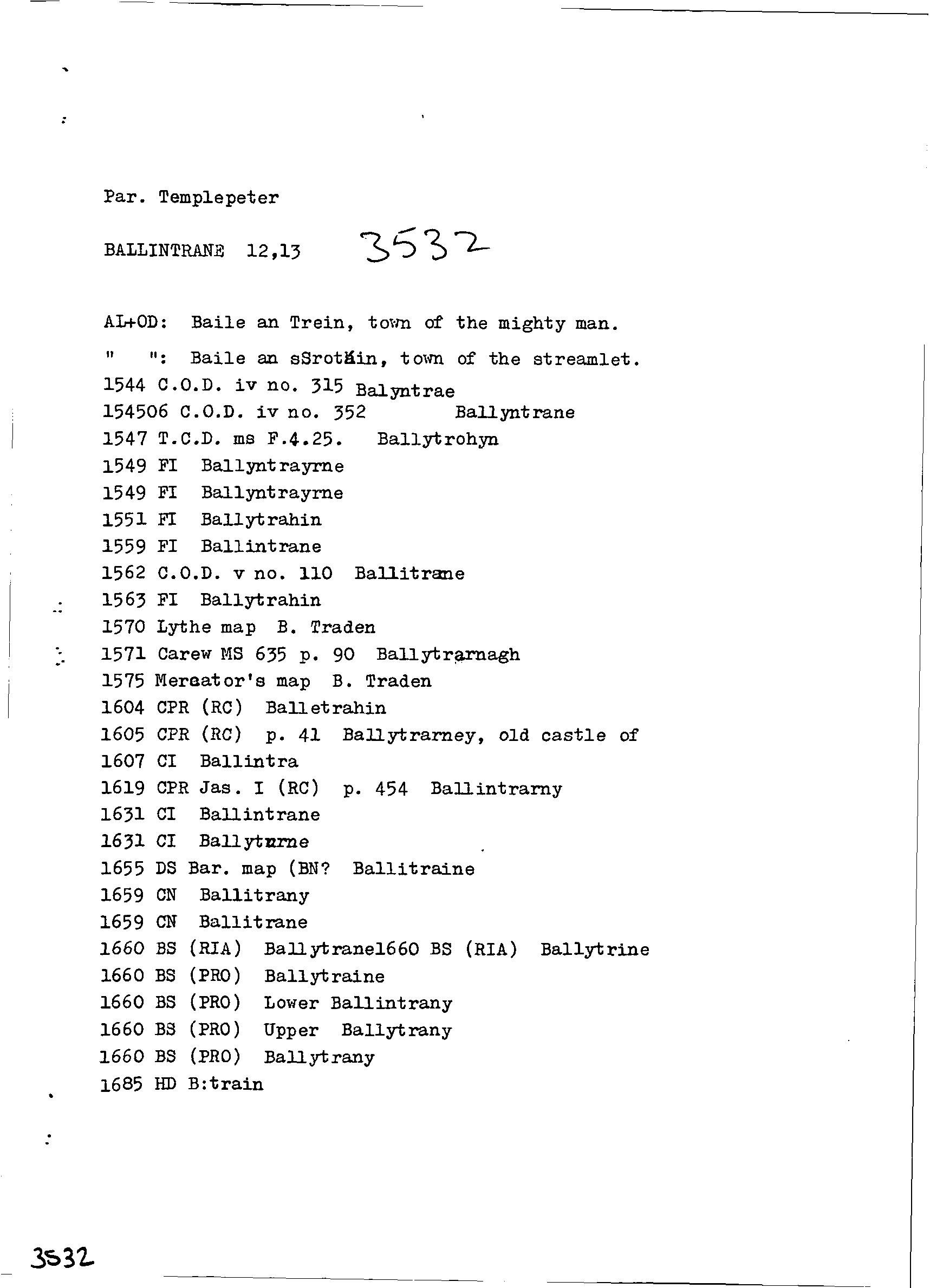

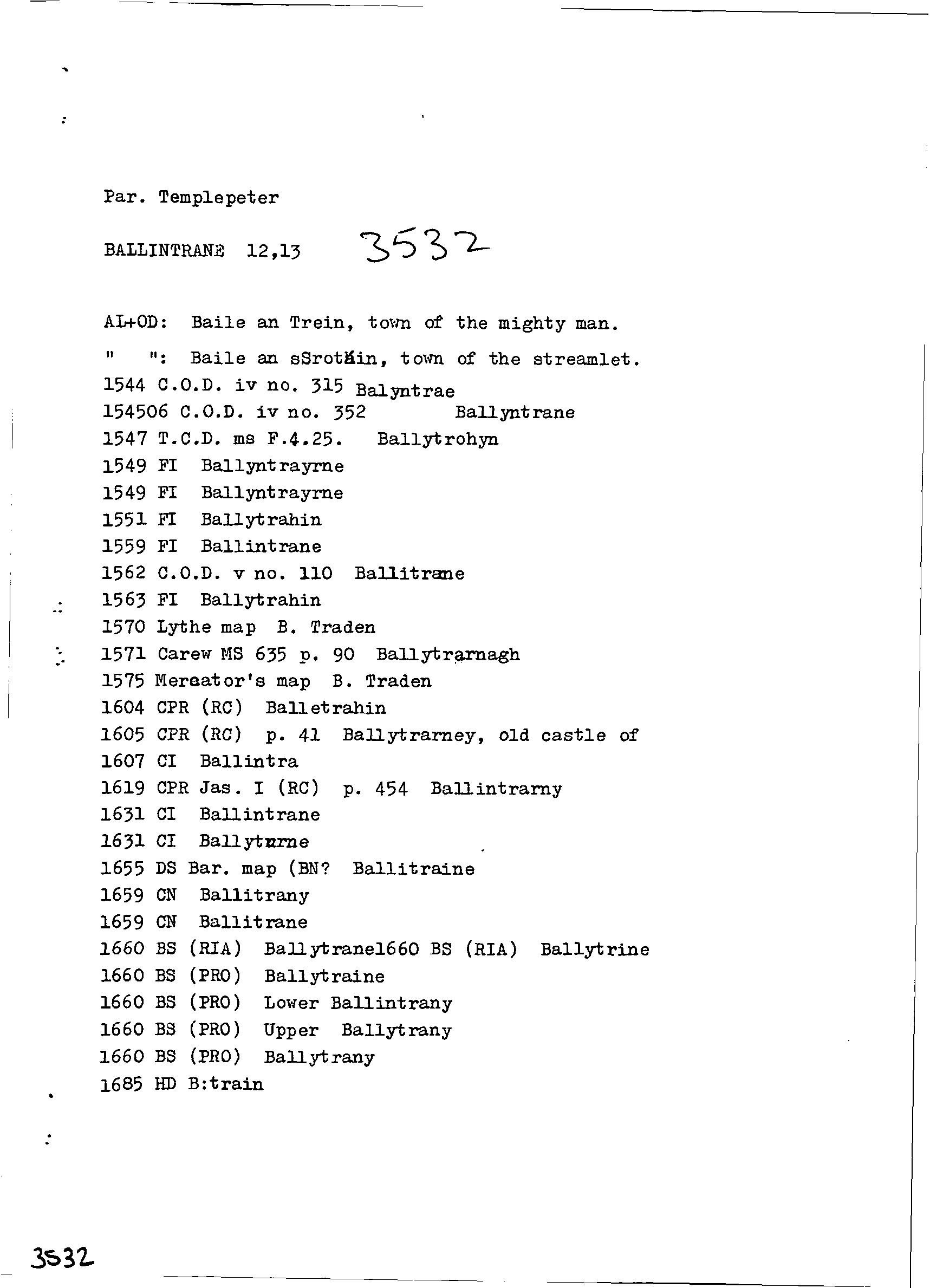

Historical references

| 1544 |

Balyntrae

|

COD Imleabhar: iv, 260

|

| 1545-1546 |

Ballyntrane

|

COD Imleabhar: iv, 287

|

| 1547 |

Ballytrohyn

|

TCD Leathanach: F 4.25

|

| 1549 |

Ballyntrayrne

|

F Leathanach: 340

|

| 1549 |

Ballyntrayrne

|

F Leathanach: 340

|

| 1551 |

Ballytrahin

|

F Leathanach: 719

|

| 1559 |

Ballintrane

|

F Leathanach: 140

|

| 1559 |

Ballyntrane

|

F Leathanach: 140

|

| 1562 |

Ballitrarne

|

COD Imleabhar: v, 126

|

| 1563 |

Ballytrahin

|

F Leathanach: 504

|

| 1570c |

B Traden

|

|

| 1571 |

Ballytrarnagh

|

Carew Mss. Leathanach: 635, 90

|

| 1595 |

B Traden

|

|

| 1604 |

Balletrahin

|

CPR Leathanach: 52

|

| 1605 |

Ballytrarney, old castle of

|

CPR Leathanach: 41

|

| 1607 |

Ballintra

|

Inq. Lag. Leathanach: 1 J I

|

| 1619 |

Ballintrarny

|

CPR Leathanach: 454

|

| 1631 |

Ballintrane, le bawne

|

Inq. Lag. Leathanach: 27 C I

|

| 1631 |

Ballyturne

|

Inq. Lag. Leathanach: 27 C I

|

| 1655 |

Ballitraine

|

|

| 1659 |

Ballitrane

|

Cen. Leathanach: 353

|

| 1659 |

Ballitrany

|

Cen. Leathanach: 356

|

| 1660c |

Ballytraine

|

BSD (Ce) Leathanach: 72

|

| 1660c |

Lower Ballintrany

|

BSD (Ce) Leathanach: 72

|

| 1660c |

Upper Balltrany

|

BSD (Ce) Leathanach: 72

|

| 1685 |

B:train

|

|

| 1833 |

Ballintrain

|

|

| 1839 |

Ballintrane

|

BS:AL Leathanach: Ce 51, 9

|

| 1839 |

Ballintrane

|

Cary, Capt., Agent:AL Leathanach: Ce 23, 4

|

| 1839 |

Ballintrane

|

Downy, Rev.:AL Leathanach: Ce 23, 4

|

| 1839 |

Ballytraine

|

DS:AL Leathanach: Ce 51, 9

|

| 1839 |

Ballintrane

|

Kinsella, W.:AL Leathanach: Ce 51, 9

|

| 1839 |

Ballintrane

|

Murray, H.:AL Leathanach: Ce 51, 9

|

| 1839 |

Baile an tráin (tsruthain?)

|

OC:AL Leathanach: Ce 51, 9

|

| 1839 |

Baile an tSrotháin, town of the streamlet

|

OD:AL Leathanach: Ce 23, 4

|

| 1839 |

Baile an Tréin, town of the mighty man

|

OD:AL Leathanach: Ce 51, 9

|

| 1839 |

Baile an tSrotáin, 'town of the streamlet'

|

OD:AL Leathanach: Ce 51, 9

|

| 1839 |

Ballintrane

|

Rec. Name:AL Leathanach (AL): Ce 23, 4

|

| 1839 |

Ballintrane

|

Rose, J.:AL Leathanach: Ce 51, 9

|

Please note: Some of the documentation from the archives of the Placenames Branch is available here. It indicates the range of research contributions undertaken by the Branch on this placename over the years. It may not constitute a complete record, and evidence may not be sequenced on the basis of validity. It is on this basis that this material is made available to the public.

Archival and research material provided on this site may be used, subject to acknowledgement. Issues regarding republication or other permissions or copyright should be addressed to logainm@dcu.ie.